|

HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDRECONSTRUTION OF ORGANISTRUM DOCTORAL THESISCONCERTS |

| CONFERENCESlutheria fairsDiscography VIDEOSPRESS RELEASES Contac |

THE

ORGANISTRUM IN SPAIN |

|||

historical background |

|||

The “organistrum”, which formed a fundamental part in the evolution of monastic music throughout Europe in the High Middle Ages, is known to us through the iconography that has lasted to these days. The wide range of musical instruments represented pictorially from the last third of the 12th century and through the following two and a half centuries in Spain, is shown within the musical iconography of the period, particularly in biblical passages from St. John’s Revelations. The “organistrum” appears in European iconography from the 10th century until well into the 15th century. Early versions are shown being played by two people. Later, with the “organistrum” for one person, there continued to be a harmony box and its casing. This “organistrum” was smaller than its predecessor. The musician’s task was to activate the instrument, play it and, sometimes, to sing. In a Europe dominated by Latin and Gregorian chants, the “organistrum” was principally a religious instrument which was capable of establishing a permanent and constant sound, due to its bass string, which is known these days as the pedal note. Usually, musical instruments have been changed little by little

throughout the centuries as new shapes, names and technical advances

have appeared. |

|||

|

|

||

(Fig 1). "Organistrum"

of the door of San Miguel de Estella, Navarra c. XII. Spain |

(Fig 2). "Organistrum"

of the door of Sarmental, catedral de Burgos c. XIII.Spain |

||

| BIBLICAL REFERENCES | |||

The visual representation of the “organistra” began with the stone sculptures which appeared as part of church and cathedral doorways throughout Europe. It is very common in the Spanish iconography to find a representation of the 24 elderly men of the Apocalypse carrying their musical instruments. This takes the form of a kind of Senate complete with thrones, crowns and white clothing, all of which symbolizes the triumph of the Chosen. Above all, Revelations is intended to pass on a message of hope to all Christians. This message was intended for the Church, which was in a critical situation in the 1st century, when the most difficult test of faith would have come in the form of Roman persecution. Revelations is the final book of the New Testament, and of all the Sacred Writings. Its meaning is the revealing of something that was hidden. Its characteristics are: · Its author according to the Christian tradition is St. John. Words are used with images to give full meaning. · The author of Revelations describes visions featuring symbols, voices and heavenly apparitions, mysterious numbers and phenomena of nature. · The apocalyptical visions are intended to show both the soon-to-be and far-off future of mankind. Revealing the final triumph of God is a way of telling the people to maintain faith come what may. · The apocalyptical writings create the impression that the arrival of Jehovah is imminent. St. John sent his writings to the cities of Asia as a type of circular. Thus, the book acquires the feeling of a conversation between God and His people. Hope is based within the power of God, Creator of the Universe, and in Christ’s victory. He will defeat all the powers that fight against His reign and He will remake the created Universe. If we look at some biblical passages, we will better understand the iconographic meanings of our doorways: REVELATIONS Chapter 5, Verse 8: Chapter 4, Verse 4: Let us now emphasise some of the 23 representations found within

Spain which help to enrich our knowledge of the “organistrum”’s

place within medieval music. |

|||

| "ORGANISTRUM" of the door of SAN MIGUEL DE ESTELLA. (1147). Navarra. spain | |||

In the second half of the 12th century, Navarra featured great sculptural activity of significant richness as it lay at the beginning of the pilgrim’s Road to Santiago de Compostela. We are going to focus on the Northern doorway of the church of San Miguel de Estella, which was built in the second half of the 12th century. The “organistra” are located on the second archivolt, dedicated also to angels, the elderly men and prophets. They are placed symmetrically, in the semi-circular arch, among the elderly men of Revelations and, in the second row of this archivolt, there are two pairs of these elderly men chanting the new canticle around the Creator. Each of these pairs plays an “organistrum”. After reconstructing the instrument, when we compare it with others from Spain and Europe, we are left in absolutely no doubt that the “organistrum” from Estella was the most technically advanced model at that time. It established guidelines for where the keyboard should be arranged in the “organistra” and in the modern hurdy-gurdies, which, in the following centuries, have changed in their shape but not in their function. The image of the second archivolt on the right-hand side shows the difficulties of the elderly musician in holding and playing to the axle to make the instrument’s sounds. The elderly musician, who plays with both hands on the keyboard, is positioned in such a way as to show us the possibilities of the instrument for the playing of compositions of a fair speed and complexity, even when the compositions of the period were not very daring. This is the “organistrum” which served as a reference point for all others. In most doorways it is positioned in a favoured place. We can see it twice in Estella, on either side of the bell, with Christ enveloped in an ornamental frame (in the shape of four almonds joined to form four arms, with the image in the join). Due to their aesthetic value, the six niches sculpted in the side

of the instrument attract one’s attention. It would seem logical,

considering the symmetry of almost all musical instruments, that

there would be another six niches on the other side. Given these

initial parameters and knowing that all the doorways were painted,

it is to obtain an idea of the great wealth and of the admiration

which would have been caused by the “organistrum” within

all those privileged to watch and listen to it. |

|||

| "ORGANISTRUM" of the door of GLORIA. (1188). Santiago de Compostela, La Coruña. spain | |||

The “Portico de la Gloria” is one of the most accurate representations of St. John’s Revelations, featuring the aforementioned 24 elderly musicians. The “organistrum” is situated in the upper quadrant of the semi-circular arch where the 24 elderly men are shown. It is the only instrument of those shown that requires two people for it to be played. It is very rich in Moorish interlacing and a reference point for any dealings with the instrument. Its keys are not pressed but pulled, according to the representation, so it seems very simple to play. Thus, it is an instrument designed to accompany not to lead.

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|||

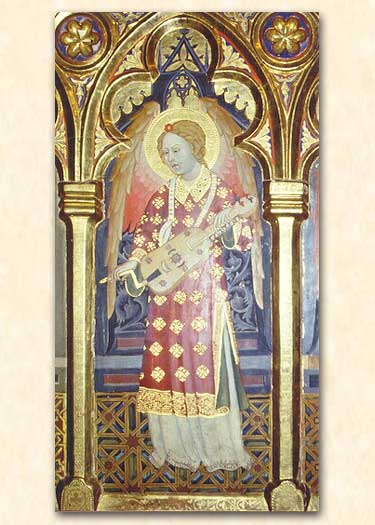

"ORGANISTRUM" DEL TRÍPTICO DEL MONASTERIO DE PIEDRA. ZARAGOZA. (1390) |

|||

MONASTERIO DE PIEDRA (ZARAGOZA). 1390 The Royal Academy of History in Madrid, apart from holding manuscripts and printed matters relating to Ancient, Medieval and Modern History, contains one true outstanding gem: this is the reliquary triptych from the Monasterio de Piedra of Zaragoza. Herein are represented 8 musician angels with musical instruments from the time – which are to be found in the two lateral plates of the triptych. The third angel on the left, in the right-hand plate of the triptych, is holding and “organistrum”. It is, without a doubt, the connection between iconographic medieval representations and pictorial representations of the hurdy-gurdy. The extremely detailed decoration, as with its technical and musical aspects, allow us to rebuild the “organistrum” almost precisely. The first aspect this picture gives us is the variety of woods used for their colour, shape and hardness to obtain more durability in its most critical elements, the pegboxes and the bridge. The lateral hoops of the harmony box are bent due to the great attention to detail of the painter who intended to draw the grain of the wood to show us its angles. The cover of the harmony box is slightly bent lengthways to allow the sound to be expelled. The handle was detachable to make the transport of the instrument easier. The handle was separate from the axis so as to avoid the inevitable technical problems as the simplicity of the tools in those times made it very difficult to put both the axis and wheel on with the necessary precision required in the creation of an instrument which was this complex. |

|||

HURDY-GURDY: A DEFINITION |

|||

The hurdy-gurdy began to appear in the 15th century in Europe, and here it has remained, achieving a certain degree of dissemination. The hurdy-gurdy is a stringed instrument which is derived from the “organistrum”. The main difference between them is that the hurdy-gurdy has its casing on the harmony box and the “organistrum” has it directly after this box. It has got a wheel, which is rubbed with resin and turned by the handle, which plays the melody and bass strings. The first evidence of this instrument dates from the Renaissance. The hurdy-gurdy is an instrument which is named in different ways, even within the same country. For example, it is called “zanfona” in Galicia (Spain) – and it is this name that has been colloquially adopted by almost all current Spanish musicians. However, it is called “vielle à roue” in France, “hurdy-gurdy” in England and “die Drehleier” in Germany, etc. |

|

||

(Fig 5). Hurdy

- Gurdy of Nigel Eaton played by Germán Diaz. 20 th Century

in Navacerrada, Madrid, Spain |

|||

| CONCLUSIONES GENERALES | |||

GENERAL CONCLUSIONS 1. The name “organistrum” seems to be the most appropriate for this instrument. The “organistrum”, complete with written name, is situated next to a zither and a lyre in the musical allegory of the “Hortus Deliciarium” miniature (1176 – 1196) by Abbess Herrade de Landsberg. The “organistrum” is called “sinfonia” in some works, but this is not correct according to the definition given by Saint Isidoro (560 – 636) in his “Etymologies”. The “sinfonia” was defined as: “a kind of pierced drum like a sieve which is banged on both sides simultaneously or alternately, producing a very pleasant harmony due to the mix of high and low sounds”. Therefore, thanks to the age of this particular definition, the mistakes of some authors are made apparent. Another relevant factor is translation, as the different European languages have evolved and grown away from the predominance of Latin. 2. The “organistra” of the Portico de la Gloria and Estella, in Spain, have 12 keys in an octave, meaning they are chromatic instruments. Over the next few centuries, some representations show them to be diatonic, with 8 or 10 keys. The present hurdy-gurdy is, thanks to its evolution, a melodic instrument, chromatic and consists of two octaves (24 keys). 3. We must be careful with the notion of linking the name of “organistrum” with that instrument played by two people, as mentioned by some authors. In the Puerta del Sarmental of Burgos Cathedral, we find a smaller “organistrum” for one musician, which has the same shape as the one at Santiago de Compostela. The same thing is repeated with the “organistrum” from Leon Cathedral.

|

|||

4. The “organistrum” from Estella is an instrument which can create melodies capable of transmitting strength, feelings and, at the same time, playing the scores, or musical notes, from that time and, undoubtedly, other tunes which musicians could adapt. According to a contemporary writer: “If at a given moment even the most experienced singer could forget his lines, there was little for him to do save become one more listener”. We can see the dawn of improvisation in this battle between learning and the retention of songs in the memory. “In the 14th century, Jacques of Liège complained that some singers were distorting Gregorian chants into common music”. The instrument that spoke to the ears of the authority figures who needed musical pleasures to show they were different from the village people. Thus, for example, the “organistrum” of Estella can play both old melodies and modern arrangements.

5. Following on from the master-designer from the Monasterio de Piedra, at Zaragoza (14th century), the later builders of wheeled instruments have both known and improved on each detail of the “organistrum” and “hurdy-gurdy” continually down to our times. This knowledge spread through Spain and the rest of Europe. Nowadays, most of the elements that make up the “organistrum” and hurdy-gurdies are common to builders in Spain, Europe and other parts of the world.

6. The picture “El Jardin de las Delicias” by “El Bosco”, painted between 1500 and 1516, is one of the first representations of what is the current diatonic hurdy-gurdy, where the casing is mounted on the harmony box.

|

|

||

| (Fig. 6). Partial view of the picture "El jardín de las delicias" de "El Bosco", XVI th century. Museo del Prado, Madrid . Spain | |||

7. After proving through practice the possibilities

of the “organistrum” from Estella in several different

Spanish locations, it would probably not be much of a risk to suggest

a few reasons for its disappearance from the music scene. Thus: 8. The polychrome applied to the “organistrum” recovered

from the doorway at San Miguel de Estella, is intended to contribute

to the resulting sounds from wooden instruments, and the hypothetical

embellishment of it, as with the polychrome of all the doorways,

would combine to make a faithful reconstruction of the instrument. |

|

||

|

|||

Miriam Serck-Dewaide, of the Royal Institute of Artistic Heritage in Brussels, made a polychromatic analysis of the instruments from the Portico de la Gloria in the chapter dedicated to: “The finishings of musical instruments of the 12th century and the copying of those from the Portico de la Gloria in Santiago de Compostela”. She concludes that there is a difference between polychroming stone and polychroming wood, but comes to no clear conclusion about the possible finishings of “authentic medieval musical instruments”. Without wishing to delve further into polychromatism – as the idea of colourings could lead to another, bigger tome – it can be concluded that the colour of the “organistrum”, with all its techniques and chromatic tone possibilities, contributes to:

During the history of mankind, the greatest inventors, thinkers, mathematicians, etc., have been keen observers of nature. Everything belongs within an order. Thus, colour with its chromatic range, musical harmony with its guidelines, numbers with their magic value, and, in general, each of the known arts of different ages, form a kind of universal discipline which can be assimilated, accepted or rejected as much by figures of authority as by ‘less educated’ people. The arts, in general, are there so that human beings can research into or discover the joys that might be encountered.

|

|||